When you look at something you are often looking through or around something else; a window, a door,

under a tree, or through your glasses (my constant view frame). People also

like to frame pictures and objects; it makes the picture more focused, and the

object more important in some way. Paintings and photographs often use a frame

within the image itself: for instance the view of King Charles Street, Whitehall,

London (top, above) or the Tower Bridge (both from the Picture Book of London

published by Country Life in 1951).

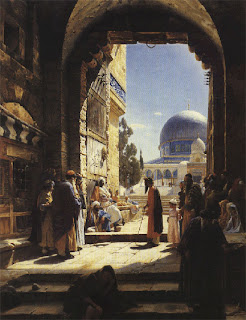

Painters have always played with framing devices, using some

foreground object to give scale and frame the view. The painting above by

Gustav Bauernfeind called, At the

Entrance to the Temple Mount, Jerusalem, is a straight forward “through the

arch” approach, mirroring the photograph at the top of the page.

Of course conveniently located arches are not always

available, so the usual fallback tactic is the side of a building, or looking

out from under a part of a building, such as Egyptian Landscape with a Distant View of the Pyramids by David

Roberts.

Paintings of a town or city provide windows, doors, arches

and other manmade foreground opportunities. In the country you need to use an

entirely different set of objects. Albert Bierstadt used mountains, trees and

clouds to frame his Landscape, above.

In the Deer at Sunset,

Bierstadt used what I call the “L” frame, a contrasting form following the

bottom and side of the image. Such a “frame” helps focus the image using a

fairly commonly occurring form. In this case it is the rocky base of a cliff

and the shadow cast by the cliff.

In The Conquest of the Amazon by Antonio

Parreiras, the shadowed tree trunk and people in the foreground form the frame

to the ceremony taking place in the sunlit clearing.

Frederic Edwin Church was always able to capture the drama

of any landscape. His painting called The

River of Light uses not only natural lighting effects, but the foreground

frame to heighten the effect.

Terra natal by

Antonio Parreiras includes enough detail in the darker “frame” area, to make it

the focus of the viewer’s interest.

Winslow Homer didn’t use framing very often (tending to

center the focus), but when he did, as with At

the Window, he broke the rules in the most interesting way. In this case he

contrasts the frame with the view out the window, giving the frame the primary

emphasis.

La Siesta, Memory of

Spain is a typical composition by Gustave Dore, using strong foreground shadow,

and high contrast and detail to draw the eye.

Architectural renderings can be easily improved by using an

“L” frame. Green Study by Aleksander

(Olek) Novak-Zemplinski takes an already interesting abstract sculpture, and

adds immediacy by framing it with interior space.

ASB Bridge Kansas City

by Dick Sneary puts the bridge in context, while giving depth to the rendering.

W-Project Theoretical

by Tomoaki Hamano creates a frame and a balance using trees and foreground

objects. The inclusion of the “professorial statue” gives a nice narrative to

the otherwise dry subject.

Frames can be made from almost any object. People are always

around just begging to be placed in a rendering, and most locations have trees

and adjacent buildings. Don’t worry too much about the accuracy of the placement

of foreground objects; there is a surprising degree of forgiveness when you get

a composition right.

A caveat for all posts on composition.

You don’t

want to produce total chaos.

You don’t

want to create banal order.

You do want

to entice, hint, and suggest.

You want to

create mystery, even if the subject appears to be obvious.

- Composition Part 1 - Architectural Illustration

- Composition Part 2 - The Golden Section & other crutches

- Composition Part 3 - Dark Spot

- Composition Part 4 - Light Spot

- Composition Part 5 - The Cross

- Composition Part 6 - The Pyramid

- Composition Part 7 - Circle

- Composition Part 8 - Diagonal

- Composition Part 17 - Value Studies- Composition Part 2 - The Golden Section & other crutches

- Composition Part 3 - Dark Spot

- Composition Part 4 - Light Spot

- Composition Part 5 - The Cross

- Composition Part 6 - The Pyramid

- Composition Part 7 - Circle

- Composition Part 8 - Diagonal

No comments:

Post a Comment