Just to be upfront about this post, I DO NOT want to teach 2

point perspective. There are plenty of books and websites devoted to laying out

perspectives by hand and computer. If you are looking for a basic tutorial,

stop and look elsewhere.

If, however, you know the basics, this post may be of use to

you because it will address some of the problems normally found in perspective

layouts.

In high school I took a class in architectural drawing. It

involved designing a relatively simple (indeed bland and boring) house, and

then producing a fairly complete set of working drawings. In addition, the

teacher allowed extra credit for the production of a rendered perspective of

the house.

I had never created a perspective layout, but after checking

out an example, I found it an obvious trick. The whole process seemed easy and

self-evident (I know that this sounds like boasting, but it is a true story). I

imagine that I have undervalued the skill because of that early facility that I

stumbled upon.

In addition to this, I have found (along with every other

architect or artist) that computers make perspective layout obsolete.

What I’m trying to say is that teaching perspective seems a

boring waste of time to me.

So… I’m going to touch on the basics of 2 point, and then

get on to making a few points about distortion.

If you read my posts on one point perspective you know that

there isn’t much difference between 1 and 2 point perspective. The idea is the

same, and one can be developed from the other (and vice versa), especially if

you are working on a rectilinear floor plan.

So… here is a quick

and dirty review of perspective layout.

Take a site plan of your building (it is best to use a roof

plan or something showing the general setbacks and shape of the building) and

pick a point to view it from. Draw a line from the approximate center of the

building to the “station point” (where

the viewer is standing). Strike a line called the “picture plane” perpendicular

to the line through the station point. This line can be placed practically

anywhere, but for simplicity is usually touching the closest corner of the

structure (as shown).

The “picture plane” is the same thing as the dotted paper on

a hinged frame, illustrated by Durer above, except that it deals with plan

only. The vertical dimension comes later.

Next, strike lines parallel to the elevations and running

through the station point. Mark where these lines intersect the picture

plane. From these intersections drop lines as shown. Mark a “horizon line”

parallel to the picture plane (again, this can be placed anywhere above, below

or on the picture plane, but for clarity is usually placed below the station

point). Where the drop lines intersect the horizon line mark your “vanishing

points.”

Now draw another line parallel to and slightly below the

“horizon line” (“h” above). Call this the “ground line,” or “g.l.” The relation

of the “g.l.” to “h” will control the height of the viewpoint: if below the “h”

line, the viewer will be above ground (and with greater distance you will have

an aerial view); if above the “h” line the viewer will be below the base of the

building (normally used if the building is on raised ground with the viewer

looking up at it). Next drop a line from the point where the picture plane

touches the building. This is the “height line,” or the line on which the

vertical dimension is measured.

Now draw lines connecting the station point or “s.p.,” with

each of the major plan corners. In this case I’ve connected the 4 corners of

the building as well as the ridge line of the roof. Note where these lines

intersect the picture plane, or “p.p.” (red dots).

Next drop lines from the p.p. intersects to the area

around the “h” and g.l. These lines are the corners of the building as seen

on the perspective drawing itself. But what about the vertical dimension? For

that you must draw or paste the elevation(s) (drawn to the same scale as the

plan used), with the ground at the same position as the g.l. Strike lines

across until they meet the height line (“h.l.”) (red dots). Drawing lines

that connect these marked heights on the h.l. to each vanishing point

(“v.p.”) will create a frame for the building in perspective. The box portion

of the house is described by the lower two vanishing lines, while the ridge

line from the plan and the top vanishing line mark the position of the ridge

in perspective.

The result (because we chose a high viewpoint) is a low

aerial view.

Here ends the quick

and dirty review of perspective layout.

And here begins a collection of comments on two point

perspective.

As with the one point process, once you have a rectilinear

grid set up, you can describe any shape. Inscribe an oval in the top and bottom

of a cube…

… and you have a cylinder.

Add shade and shadow, and you are on your way to modeling

reality.

As I noted in the quick and dirty review of perspective

layout above: if your ground line is above the horizon line, you are

underground; if your ground line is below the horizon, you are in the air

(above ground), and if your “ground line” is in the same position as the

horizon, your eyeball is rolling around on the ground (look out for ants!).

Distortion is the bane of the inexperienced perspectivist,

but it is easily avoided. The usual mistake is to place your viewpoint, or station

point, too close to the building being drawn. You might think that a skyscraper

would look better within the limits of the surrounding buildings, but

distortion at the top would be very noticeable.

The additional problem of placing the object at the edge of

vision will be addressed.

In this layout of a building in London, done very early in

my career, the topmost cornice is simply too angular to be believed. Moving

the station point 100 feet back would have fixed that without anyone noticing

the added distance from the building generally. (Note also the building plan

floating over the upper part of the building and on into the sky.)

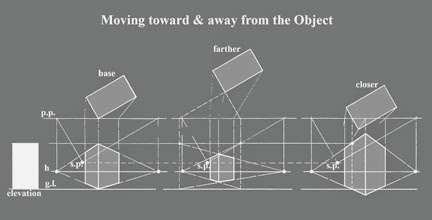

The diagram above shows a building being moved farther away

from and closer to the viewer. When you move farther away the building seems to

flatten, while the close view seems to have an awkward distortion.

Also note on this diagram the relation of the building plan

to the “picture plane” or “p.p.” As I

said before, you can place the “picture plane” anywhere on the layout, but you

will have to adjust the “height line” to make it work.

Viewpoint placement will also affect the perceived depth of

the final rendering. The photos above are of the same house; the left viewed

from just across the road (shot with a normal lens), and the right seen from

the middle of the adjacent field (shot with a telephoto lens). The “Telephoto”

view is not normal because it would only be a small part of a larger view under

“normal” conditions.

In the diagram above, the left is a “normal” view (as you

experience an object set in front of you), and the right is a “telephoto” view

(seen through binoculars or a telescope). To insure a “normal” view you should

follow the 30 degree rule: place your “station point” at the point of a 30

degree triangle formed by the two outer corners of the building, and the

“station point”. Using a 30/60 triangle (colored in tan above) to locate the viewpoint

makes the rule an easy one to follow if working by hand.

Besides getting distortion at the top of tall buildings, you

can have distortion at either side of a drawing (at the edge of vision). Each of the 3 layouts above show the same

barn, but each (reading from left to right) places the barn to the right, the

center, and the left of the direction the viewer is looking. You can see that

the side of the barn is stretched out in the view on the left, while the end of

the barn becomes dominant in the view on the right. On its own the barn doesn’t

look too bad, but if included with a group of buildings, or a single sprawling

building, it will look awkward.

The layout of the New York Stock Exchange Main Trading Floor

(above) was completed when I was still learning to do layouts. It not only has

distortion occurring in the ceiling, but it is an unfortunate mix of 1 and 2

point perspective. At the beginning it was important to see the end and right

side of the room. Later it was decided that the left side of the room should be

shown also. The wall on the left is reasonable, but the truss structure becomes

rather overbearing in the upper left corner since it as at the edge of a

person’s normal vision.

Not every building is rectilinear. Some streets and

buildings are acute or obtuse angles. What to do? If the entire building is

designed on some angle other than the usual 90 degrees, you can simply use that

new angle as though it were the same as a normal right angle. In the example

above all walls are parallel to one of the front elevations. If each wing was

layed out as a separate right angle grid, then you would need 4 vanishing

points to complete the drawing.

In the drawing above there were a number of vanishing points

used, corresponding to the various surfaces on the building. The blue wall

followed the street angling off to the left. The orange wall was perpendicular

to the front façade, and angled in from the blue wall. The yellow billboard was

angled out from the street wall to give people a better view of the sign.

Many buildings are built on flat, or almost flat sites. In

those cases the vanishing points for the building and the streets are on the

horizon.

If, on the other hand, the building you are drawing is on a

steep street you will find the vanishing point for the adjacent street above or

below the vanishing point of the building.

Distortion is also found in computer generated rendering,

and can be eliminated using the same tricks. Interestingly, distortion was, and

still is occasionally, emphasized to give an image a futuristic look.

Next post… historic

examples of perspective layout (and comments on same).

Other posts on Perspective:

Perspective - Two Point Perspective -

Distortions & ComplicationsPerspective - Three Point Perspective- Hand & CAD

Super-Duper site! I am Loving it!! Will come back again, Im taking your feed also, Thanks.

ReplyDeleteCertified Precision Roofing

Articles of furniture like this that help you optimize the available space in your house without making your house look like a furniture showroom are termed modular furniture.

ReplyDeleteHouse & Garden