Being an

architect, and having spent an inordinate amount of time being a professional

purveyor of 3 dimensional illusions, the following post might seem odd…

I just

stumbled across the drawing above in my files. It is from a July 2012 Wall

Street Journal review of a Gustav Klimt exhibit at the Getty Center. It

fascinated me then, and does now; but why? It is simple to the point of being

crude. The face is nearly invisible, and the black clothing dominates without

informing. It isn’t particularly beautiful, or balanced, or even entertaining.

But it still speaks to me.

The answer,

on reflection, is the creative tension between the flat surface and the three

dimensional illusion. Yes, there isn’t much 3 dimension to go with here, but between

the shape of the black dress and hat, and the suggested face, it is a complete

likeness.

Klimt was

quite capable of creating a three dimensional illusion on paper or canvas, but

he was fascinated by the flat, graphic qualities of church icons. The contrast

between stylized illusion and flat sheets of gold foil was a new and exciting

idea in the established (dare I say dull) world of Beaux Arts painting, with

its emphasis on the illusion of three dimensions.

The result (Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906) is striking.

It is a realistic portrait, but the overall effect is abstract; like a

designer’s material board with a color photograph of a woman pasted in.

Now, this of

course was not the first time that serious artists had used flat expanses of

color. Rembrandt left many paintings unfinished. His Portrait of the Artist’s

Son Titus leaves the background as a dark scrumb, and rendered the body with a

few brush strokes over an undifferentiated brown base. This however, was not a

revolt against three dimensionality, but a short cut in an artistic experiment.

Pierre de

Valenciennes was a landscape painter of some skill in the late 16th

century. His Villa Farnese - Two Poplar

Trees features a flat blue sky along with flat shapes for the walls of the

villa. But it is an exception to his usual painting style, so I wouldn’t call

him a precursor in any way.

With the

high point of the Beaux-Art influence came the birth of artistic protests. Berthe Morisot With a Bouquet of Violets

by Edouard Manet (1872) is a surprising match for Klimt’s drawing above. The

black of the hat and dress are barely modeled, the background is largely blank,

but the face is realistic. And, the effect is created on purpose.

Self Portrait by James Whistler, at about the same

time, is also flat by design. In this case the painting calls to mind

Rembrandt’s hurried brushwork. The idea was to elicit the sense of reality

while being blatantly two dimensional.

On the other

hand, The Cowboy by Frederick

Remington (1902), is a purposeful use of flat color to set off the well modeled

horse and cowboy. And there are plenty of other paintings by Remington which

use the same trick.

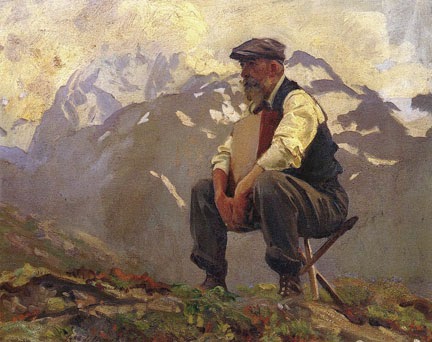

Sargent,

about whom I have already posted, used a similar technique in Reconnoitering (1911).

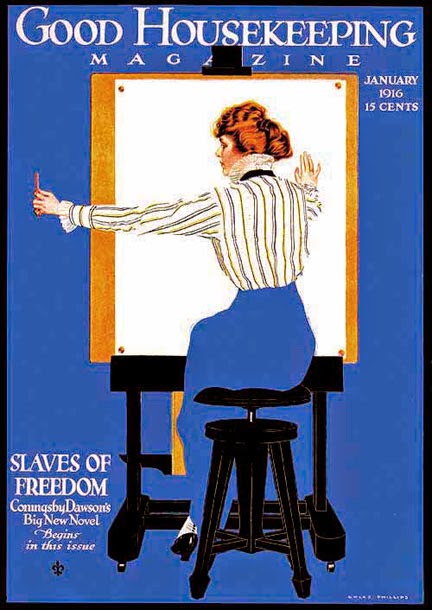

It was

natural that illustrators latched onto the idea of flat color. Reproduction of

color art was in its infancy a hundred years ago, and blocks of solid color

were easier to reproduce. This magazine cover is by Cole Phillips.

And, the

game of optical illusion could catch eyes and sell magazines. This cover is by

Valentine Sandberg.

As with all

stylistic developments (or fashions), Architects copied the look in their

renderings. Frank Lloyd Wright seemingly could not resist a new look; and this

shows in this rendering of Ravine Bluffs Bridge (1915).

Cyril A.Farey was the most famous English architectural illustrator in the early 1900s.

His rendering of the House at Silver End (Thomas S. Tait, architect) combines

the naturally flat tones of a moonlit view with the realistic detail he was otherwise

known for.

I have

occasionally played this game myself. A night view such as that above can

include flat gray skies and dark silhouettes. I never loved oil pastel for

finished renderings, but it works if you want to play around with a vague idea.

A computer

rendering, with its detailed shade, shadow and reflection is often improved

with a little simplicity. The extreme intricacy of this design by Hardy Holzman

Pfieffer was eventually simplified even more by eliminating color entirely.

I have done

quite a few montage boards in my career. Flat expanses of color are perfect

surfaces for adding plans and elevations, even if there is some gradation. In

this board the sky and street provide the background, but a vignette rendering

can have plans or elevations surrounding the building on all sides.

Just as an

unadorned wall is a good foil for ornament, a flat surface can emphasize and

highlight a 3D illusion. In the “old days” I had to rough out the possible shapes

on a pastel sketch, and usually had little time to make a decision. Today, with

computer files you can try out dozens of shapes and colors in no time. Don’t be

afraid to play with it; the results are worth it.

Postscript

(in regard to simple and complex): I attended a performance of the Ensemble

Organum and Christos Chalkias last weekend in the Fuentiduena Chapel, at the Cloisters in New York City.

It was a celebration of Saint Nicholas in Byzantine chants. What struck me was

the contrast between the simple background drone and the extremely complex

chanting of the text. The one without the other would have been boring, but

together they kept my attention. Indeed, there were times when the effect was

mesmerizingly beautiful.

Organic Blankets sale

ReplyDeleteIf you set out to make me think today; mission accomplished! I really like your writing style and how you express your ideas. Thank you.