To make an elevation projection you must

first view the world from the side.

No, this is not a trick! I mean it!

Actually, this is the normal viewpoint

of humans. Walk down a street in your neighborhood and you will be confronted

by the sides of houses. The plans may be known or completely unknown, but the

elevations are easy to see. An architect or builder will probably think in 3

dimensions while walking the neighborhood, but a “normal” person will see the

sides of the houses, and react to them first.

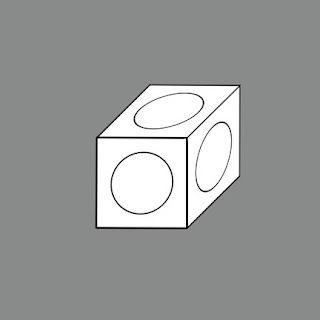

Anyway… Start with a square wall with a

circle drawn inside.

Extrude it away from you and…

Voila! A cube!

The main problem in drawing elevation

projections is distortion in a familiar plan.

If a cylinder (standing on end like a

coffee cup) is created using the original cube you will find that…

The circular plan of the cylinder seems

to be stretched into an oval. This can be easily adjusted by eye, but it is

still a problem that limits the use of this drawing type in architecture, and

makes the measurability in plan troublesome.

_____________________________________________

In spite of this, elevation projections

have been used throughout history.

Medieval map makers liked to place

recognizable structures on their otherwise confusing maps. With any luck you

could follow a road and know when you had reached your famous destination (or

not… best to ask directions of the natives at every chance).

Leonardo da Vinci could obviously think

in 3 dimensions, and knew what sort of drawing to use to explain a complex idea.

His multi-stair tower is confusing in plan, but is clear in the projection (in

fact he seems to have revised the basic idea between drawing the plan and the

elevation projection).

Auguste Choisy has already been noted

for his wonderful plan projection drawings. This elevation projection drawing

of the Basilica of Constantine in Rome is from his book L'art de bâtir chez les romans. Although the scale of each

axis (including the receding diagonal one) is the same, the distortion is

minimal.

Rob Krier’s

sketches in Elements of Architecture show elevations plus enough

diagonal depth to have a clear understanding of the 3-dimensional idea. I am

surprised that more architects don’t sketch ideas in this information rich way.

But perhaps Krier’s neo-traditional architecture makes this a logical approach,

while the flattened facades of modern architecture discourage such use.

I’m surprised

that I haven’t found more examples of this technique. Perhaps my library is

less extensive than I thought; or perhaps the design professions prefer other

ways of exploring a three dimensional idea.

This is all quite incredible...please keep it up.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading your blog thanks

ReplyDelete