Cyril Farey (1888-1954) was the most respected, prolific and

successful architectural illustrator in the 1920s and 30s. He was a favorite of

the top British architects of that day (the golden age of the British Empire),

and made 5000 Pounds, or about $200,000 per year.

But… he is largely forgotten now… There are no recent books

on his work… And, he has NO Wikipedia entry!!

What gives?

|

| Arundel Castle. |

Perhaps he was the victim of “end-of-empire” amnesia: he and

his talents were a part of the fading British Empire, while the future was to

be found in America. Perhaps he was too closely tied to the traditional

architectural styles of the past: the future was made of glass, steel and

concrete, not carved stone. Perhaps he didn’t “sell” himself to the future in a

book of beautiful reproductions: he was always busy with new commissions, and

didn’t worry about PR. Perhaps he simply lived too long; all the older

architects and critics were dead by then, and the young ignored his legacy. Perhaps

he was simply too “normal” to attract the love of the psychoanalyzed modern

world. All this might be true, but one thing was always acknowledged: he was

the British epitome of the Beaux Arts tradition.

The period 1900-1920 saw a

flowering of the art of architectural draughtsmanship. The Beaux Arts approach

to architectural drawing which placed considerable emphasis on the precise

representation of buildings enhanced by shadow and light washes, led to the

adoption of this style in many architectural schools. The Beaux Arts influence

was combined with the particularly British style of drawing, where the

motivation was to present the building as a reality; as solid form anchored

visually to the ground and existing surroundings. This combination led to the

stylistic and imaginative coloured drawings of this exceptional period. The

artists of this school combined precision in drawing with a delicate but

imaginative use of colour, bestowing a romantic aura upon the buildings. –from the catalogue produced for “Fareyland -

An Exhibition of Watercolors and Drawings by Cyril Farey” at the Gallery

Lingard, London)

|

| Midland Bank, Head Office. |

So, in spite of his awards, lucrative career and powerful

contacts, the cultural tides left him high and dry. The rejection of the Beaux

Arts tradition in the 40s and 50s also rejected Farey and his legacy. Which is

sad because…

|

| 68 Pall Mall Westminster |

His work is consistently interesting, and sometimes

breathtaking.

|

| Palais de Justice, Brussels. |

Cyril Arthur Farey was born in London, and seems to have had

an uneventful childhood, showing skill in drawing early on. He was educated at

Tonbridge School (a top English prep school), the Architectural Association,

and the Royal Academy School of Architecture. He was a brilliant pupil, winning

the RA Schools Gold Medal (1911), the Tite Prize (1913), and the Soane

Medallion (1914).

On winning a traveling scholarship from the Architectural

Association, he spent much of 1910 sketching on the continent. The following

images are from that trip.

Entrance Screen to the Nymphaeum, Villa di Papa Giulio, Rome.

A site sketch in the guise of a Beaux Arts rendered elevation.

Ponte Scaligero & Castel Vecchio, Verona. Although

unfinished, this view has the placid tone of the English “grand tour” sketch.

Figure climbing steps up to a Monastery, Perugia. This

subject calls to mind Goodhue’s Italian drawings.

Palazzo Publico & Campanile, Siena. This painting had me

doing a double take, and whispering “Aldo Rossi?”

This last view, of Piazza delle Erbe in Verona, shows

clearly his technique. A detailed line drawing precedes any watercolor work.

All details are delineated by pencil, leaving the general modeling and emphasis

to be created by the transparent wash.

This drawing of the Bowstring Bridge at Newcastle-on-Tyne,

shows a typical finished line drawing. Later in this post is a rendering of the

Sydney Harbor Bridge which suggests how the final Bowstring painting might have

looked.

Begnning in 1911 Farey served his articles (a period of

apprenticeship to a registered architect) with Horace Field, who himself was a

fine draughtsman. Farey contributed drawings to a number of successful

competitions while in Field’s office. After serving as a Captain in the Royal

Army Service Corps during World War I, he returned to field’s office to lead a winning

competition entry for the Civil Service War Memorial.

Farey worked for a while as an assistant in the office of

Ernest Newton, where he met fellow perspectivists, Thomas Hamilton Crawford and

Alick Horsnell. In the same period he became aquainted with A.G. Shoosmith (an

architect and lifelong friend); and (fellow perspectivists) Charles Gascoyne,

Robert Atkinson, James Whitelaw and Philip Hepworth. He eventually set up independent practice and

had considerable success in both competitions and commissioned illustrating. The

image above is a building advertisement printed in a newspaper (thus the black

and white ink drawing, which was an unusual technique for him, but perfect for

reproduction in a newpaper).

Palais des Papes, Avignon. For some reason this painting’s

colors make me think Renaissance.

Fountain of Neptune, Piazza di Signoria, Florence. Rather

modern, don’cha think?

Palazzo Ducale, Venice. Note the unfinished edges on this

painting; bold, no?

Following the war Farey seems to have settled into a career

of unrelenting work punctuated by forays onto the continent to draw and paint

for pleasure. I can completely empathize with this pattern. The life of an

architectural illustrator is steady pressure (with fits of frenzied work),

which makes drawing into a chore. The chance to draw merely for the joy of

drawing is like a long vacation. The images above are from his 1920 trip.

On winning the Edward Scott Travelling Studentship, he spent

1922 painting in France and Austria. A few examples follow.

Chateau of Maisons Lafitte, Paris. A dynamic composition

created by knowing where and when to stop.

Schwarzenberg Palace, Vienna. Now here is an excellent

example of Farey playing the contrast game. The far end of the façade is dark

on light; the central pavilion is light on dark; and the near end frames the

center and anchors the composition. The focus of the whole thing is the

silhouetted statue.

Place des Vosges, Paris. This façade study reminds me of

Sargent in its spontaneity.

Place Stanislas, Nancy. This painting, both fine and bold,

is a showcase of early genius.

Pont Neuf, Paris. Not impressive as a composition, but the

color harmony is just delicious!

This last image, an unfinished view of Ferdinand Bridge in

Vienna, is another window into Farey’s technique. The ghosted shadow and white

ink washed sky show his eventual intentions, while the various line weights

show that the final idea was already forming while he drew in pencil. The

effect is quite mesmerizing.

By 1923 Farey was at the top of his profession. The

following are a very small sampling of the perspectives completed in the 20s

and 30s.

Tudor House, Argyll Place, 1922. A valiant attempt to focus

a long and frenetic façade.

The Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, Arch F L Wright, 1922. I

like the abstract pattern of the shadows in this painting. The color scheme is

a mix of strong and subtle.

Sydney Harbor Bridge, 1923. I could only find a tiny image

file of this beautiful rendering…

…and I’m not sure whether

this detail is part of the completed perspective, or a completely different

painting. Compare it to the Bowstring Bridge above.

Proposed War Memorial Chapel, Durham School, 1924. Another

example of Farey’s sense of color and focus.

Proposal for Carlton House Terrace. A huge, overbearing

project which becomes benign in Farey’s hands.

New Exchange, Nottingham, 1924. A bit dramatic, but charming

in many ways. Note the softening and warming of the shadows, and the spots of

hot red accents.

New Colonial Office, Westminster. Another behemoth building

tamed and civilized by watercolor.

Mansion Flats, Grosvenor Square, London, 1926. A less than

successful golden glow.

During these years, Farey was also a practicing architect.

Above is Saint George's Church Hall designed in 1926. He did quite a number of

small churches and private houses not far from his London home by Regent Park.

Cathedral of Liverpool, Edwin Lutyens, Architect, 1929. One

of the major projects of that period. Lutyens’ design is still admired for its unique

interpretation of ecclesiastical grandeur.

Midland Bank, Poultry, 1939. A bit pretentious with its

yellow ochre stone and radiating sky, but with a wonderful street scene. I

can’t help but love the name (Poultry being the old street where the eponymous fowl

were sold, but has been for some time the center of the financial district).

This perspective of The Carlton Public House, Carlton,

Nottingham, is an example of the smaller projects that Farey took on.

During World War Two he volunteered for the Civil Defense

Service, watching for German bombing attacks and assessing damage in London.

This experience and the miraculous survival of St. Paul’s during the bombing may

have spurred him to do a series of perspectives of the neighborhood around the

cathedral in 1942 (after the blitz and before Normandy).

Ludgate Hill, London. A view of the district just west of

St. Paul’s. A clunky, unsatisfying composition, but this is wartime.

Record Office, London. Interestingly abstract, but I keep

wondering why there is water everywhere.

Cannon Street Station from the Thames, London. Nicely

composed, nicely drawn, and delicate colors. A true Farey.

Saint Paul's from Stationers Hall, London. A view of St.

Paul’s from the damaged hall of The Worshipful Company Of Stationers &

Newspaper Makers. It is a document of the bombing damage, but is also a

beautiful piece of work. Note the progressive haze as the objects march into

the distance; creating order out of a potentially confusing view.

St Paul's with St. Vedast - alias Foster, Foster Lane,

London. Farey must have done some fudging to get this view, but it is another

of his curious paintings contrasting wartime chaos with architectural serenity.

Saint Paul's Cathedral from Bankside, London. Essentially a

telephoto view from across the Thames River. A very pleasing composition with a

well thought out color scheme, and spontaneous brushwork not often found in a

Farey painting.

This last view of the interior of St. Paul’s shows a feeling

for the play of textures in his renderings. The linework is exact, but delicate;

strong where contrast is needed, and fading out to describe the space. The

watercolor wash is sometime smooth and sweet, and sometimes dark or heavily

textured.

Farey published with A. Trystan Edwards, a book entitled, "ArchitecturalDrawing, Perspective, and Rendering", in 1931. The following series of

images are from a short demonstration of his technique, found in an appendix in

the book.

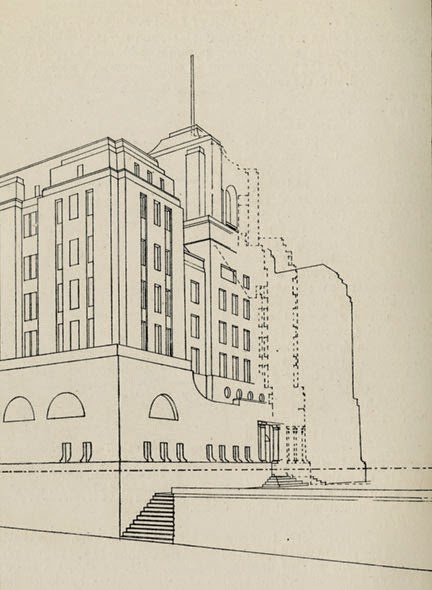

Shown above is the primary elevation of the building (plans,

site plans, and other elevations would also be consulted).

Farey, after walking the site and viewing it from all angles

decides on a rough viewpoint, and tries out several quick thumbnail sketches

from that side of the building. These sketches are not exact, but are

“guessimates” of what the building and surroundings might look like in the

final rendering. When he is satisfied with one of the sketches he heads back to

the office.

Here, Farey tries out a few quick perspective layouts to try

to match the thumbnail sketch (he is looking for the “main block” of the

building). When he gets one that looks right, he decides on the framing of the

image, and does a quick value study to establish the darks and lights. In this

case the building is a light colored stone, and all the surroundings will be

relatively dark.

With the exact viewpoint finalized, he begins the final

layout, making sure to position the picture plane so that the building is large

enough for the size of the final art. Above is the layout at an early stage.

The dotted lines are working points for the recessed façade at the center of

the building.

Here, the layout of the building itself is finished, and is transferred

to watercolor paper. The edges of the buildings planes have heavy lines, while

the stone joints are lightly drawn.

Here, the shadow lines are lightly indicated, as well as the

context of the site and entourage. This is the extent of the pencil work, and

is finalized on the watercolor paper, which is then mounted on a board.

Farey starts with the large lighter washes (the building,

using yellow ochre and grey), and moves on to progressively darker areas (sky,

using yellow ochre and cerulean blue). The view above is about halfway through

the painting process (unfortunately the book reproduction is not in color).

Here, the shadows, context, people, trees and entourage have

been addressed. Farey ends the demonstration short of his usual final detailing

because, in his words: “…the finishing is dependent on the individuality of the

artist, and it is not desirable to lay down hard-and-fast rules:” An approach

that I completely agree with.

After the war Farey continued his busy career, eventually

bringing his son into the business. His masterly touch never left him, but the modern

style of architecture did give him fewer chances to show his talent. He was of

the “old school” of architecture, favoring sensitivity to the surrounding

environment, and a loyalty to tradition and natural materials. When it came to

interpreting brick and stone, nobody could beat him.

Unfortunately, glass and steel did not interest him. As

noted in a contemporary magazine article, “To ask Farey to portray a house by

Hans Steinfinger would be like asking one’s Great-Aunt to join a nudist

colony.”

Above, Willington power station by Cyril Farey, completed in

1953; a year later he was dead. In contrast to the rather dour photograph at

the top of this post, he was said to have been a man of “great personal charm”

and a warm disposition. He was said to have been a “happy” worker, “whistling

snatches of a popular ragtime or of an aria from Puccini.” His friend Shoosmith

described him as “Gentle, sunny affectionate, a lover of life and of all things

kind and beautiful.”

I am not a watercolorist, and so this post is a bit “cheeky”

on my part. There are however, many excellent watercolor artists who have

carried on the legacy of Cyril Farey. There are two I will mention: Thomas W.Schaller is a longtime architectural illustrator, artist and author. Being a

good writer, he has a couple books out there: Architecture in Watercolor, and TheArt of Architecture Drawing: Imagination and Technique. Frank M. Costantino

is an architectural illustrator, artist and co-founder of the American Societyof Architectural Illustrators. He has been teaching seminars for a score of

years, and really should write a book sometime.

Other posts on inspirational people: