I happened on an old Harvard Magazine (March April 2009) yesterday while sorting out moving boxes in the attic. (No, I’m not Ivy, my son is). It had an article on the Supreme Court with a rendering of the Supreme Court building in Washington. The rendering was by Schell Lewis, an excellent but now forgotten architectural delineator.

It struck a chord with me. First, it was sad that such a talented artist was now completely forgotten. And second, it reminded me that I had gathered images for a blog post on him; a post that was filed away when I found so little biographical information.

Since I’m more interested in the art than the artist, I’ve decided to post what little I’ve got.

According to the 1920 census, Schell Lewis was born about 1887 in Moline, Illinois (I found a site suggesting that he was born in 1875, but that seems improbable). By 1920 he became known for his skill in architectural delineation. He worked in the office of Charles A. Platt for years, but by the late 1920s he was doing professional renderings for other architects. He was active into his 60s, with little evidence of age. The latest image I could find was from 1960.

The following is from Pencil Points magazine, vol. 2, 1921

“Though Mr. Schell Lewis has made many excellent perspective drawings and sketches he has not specialized in rendering… His charcoal drawings, made as a means of studying the designs in the office and not as presentation drawings, convey the character of the designs admirably and are done with great facility.

Mr. Lewis was born in Moline, Ill., but his family removed to New York when he was a youth. After acquiring the rudiments of drafting he entered an architect’s office in New York. Then, after a few attempts, he secured a place in the office of Mr. Charles A. Platt, in whose organization he has been continuously excepting six months with the U. S. Shipping Board and six month with Trowbridge & Ackerman.

All of Mr. Lewis’ work shows an appreciation of architectural character as well as a knowledge of architectural design.”

I first saw Lewis’s work in

Drafting Room Practice by Eugene Clute (Pencil Points Press 1928). I found an old copy in a used book store years ago. There was no biographical information, but they reproduced a number of wonderful architectural detail studies done in charcoal.

The only other story I found concerning Lewis’s work is in

The President as Architect: Franklin D. Roosevelt's Top Cottage, By John G. Waite Associates, Architects. In 1938 President Roosevelt sketched out the design for a “cottage” on his Hyde Park property north of New York City. Lewis, who did regular work for Henry J. Toombs, FDR’s favorite architect, was brought on to do a couple pencil renderings for a publicity brochure. Being a “traditional” renderer familiar with traditional architecture, he fit in perfectly with FDR’s love of the old country style of building.

Here are a few additional images which show something of Lewis’s rendering process. His preliminary sketches are nice examples of value studies produced by all artists of the time. The preliminary working out the light and dark areas ensures an image that presents the subject in a pleasing way. See my post on

Gustave Doré for more of the same, as well as all of my posts on composition.

|

| Prelim sketch for Cadet Barracks at U S Military Academy |

|

| Finished rendering of Cadet Barracks at U S Military Academy |

|

| Prelim study for an aerial view of a Church |

|

| Prelim sketch for a rendering of a Church |

|

| Finished rendering of a Church |

|

| Unfinished Prelim study for a Church |

______________________________

The following images are all of the Schell Lewis renderings that I could find on the internet. They are arranged in roughly chronological order. Comments are included as I felt the need.

|

| 1088 Park Avenue New York City, 1924 |

This and the next 6 renderings are nice examples of subtle value manipulation used to enliven otherwise dull forms.

|

| Apartment Block in New York City, 1926 |

|

| Proposed Development at Warm Springs, Georgia, 1926 |

|

| 111 John Street, New York City, 1927 |

|

| 15 East 39th Street New York City, 1928 |

|

| 1441 Broadway, New York City, 1929 |

|

| Bronx County Jail, New York City, 1931 |

_________________________

|

| Proposed Chapel at Kent School, Kent, Connecticut 1929 |

The image above was the only interior rendering that I found.

|

| Georgia Building, 1933 |

|

| Chapin School in New York City, 1935 |

The following 4 renderings are from the 1939 World’s Fair, held in New York City. Both

Hugh Ferriss and

John Wenrich did illustrations for the fair.

|

| Court of the States Building, Inner court collonnade & tower |

|

| Court of the States Building, Inner court |

|

| Court of the States Building, Spanish grouping |

|

| Court of the States Building, West court |

___________________________

|

| Band Building, 1947 |

|

| Mallory Gymnasium, Rhodes College, 1949 |

|

| Toronto City Hall proposal, 1955 |

|

| Trezevant Hall, Rhodes College, 1959 |

|

| Moore Moore Infirmary, Rhodes College, 1960 |

|

| Proposal for Mahan Hall at West Point, 1967 |

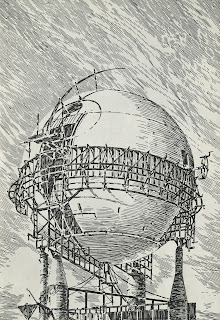

Lewis seems to have preferred pencil throughout his career, but was clearly a master of ink as well, as shown in the last two images I found. The first is copied from the internet and is very low resolution. The second image (noted simply as "brick house") is scanned from Arthur L. Guptill's classic

Rendering in Pen and Ink, and is detailed enough to show both the overall composition and the satisfying details.

|

| Burrow Library, Rhodes College, 1951 |

So, what do I take away from all this?

Schell Lewis is inspiring because he blends the large, conceptual view with the rendering of crisp detail. “Fine” artists can often get away with a broad-brush splash of emotion or symbolism (the rest is commentary). Architects, on the other hand, are usually obsessed with the details: “God is in the details”. But both scales of view are necessary.

The architectural illustrator must needs do both. Yet, it is unusual to find someone who can mix the two extremes so seamlessly as Schell Lewis did.