Plans were probably the first type of

construction drawing to be used. There are examples from 18th

dynasty Egypt (on papyrus) and from the city of Nippur Mesopotamia (on clay

tablet) around 1500 BC. Not long after this elevations show up in the archeological

evidence, and it seems an easy step from there to putting the two types of

drawings together in a single drawing. I admit that I have not found any

example of this in artifacts from the ancient world. This doesn’t surprise me much

since such drawing would have been used for on-site (draw in the dirt)

explanations to the workers, not for governmental propaganda or record

keeping).

Suffice it to say (and this is my own,

unsubstantiated opinion) that plan projection drawings must have been one of

the graphic tools of builders early on. In any case, it has been a favorite of

architects and engineers in more recent times.

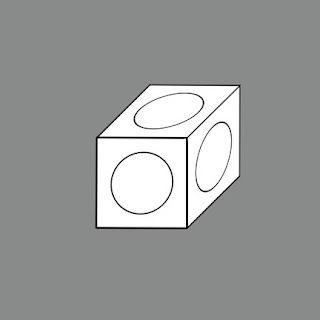

Projecting a plan into

3 dimensions is quite easy - draw the plan of an object; rotate it to any

angle; and then project the sides down (or up) from the corners.

Add shade and shadow

for a good approximation of reality.

A cylinder (in plan)

is quite easy to draw…

Just draw the circle

top and bottom, and…

Connect with vertical

lines.

Again, shade and shadow…

To draw a sphere in

plan projection, start with the cylinder in plan.

Then add cylinders from

each projected side.

The intersection of

all three cylinders will define the outside edges of the sphere.

Shade and shadow

(blah, blah, blah)… but, you might notice that the sphere is a bit off.

The pink circle shows

how much my constructed sphere has stretched. It isn’t bad, but it does point

out that the vertical projection lines of the original cube are a bit too long.

________________________________________

Back in 1988 there was a very nice

demonstration (above) showing the creation of a plan projection in Architectural Illustration Inside and Out

(by Lorenz & Lizak). The plan (left drawing) is rotated so as to eliminate

confusion in the final drawing (any angle will do, but it is best to avoid

confusing alignments in the projected walls). The middle drawing shows the

walls projected down (at this point any confusion should be obvious). The final

drawing on the right adds detail, and shades some of the planes so as to

clarify the form.

__________________________________________

The following 25 images are examples of

plan projection drawings presented in chronological order. I had no problem

finding them in my books, magazines and files. In fact I could have included

many more.

Architects over the last 100 years seem

to have had a love affair with plan projections. This is actually quite logical

for several reasons. First, architects normally design in plan before anything

else. Second, combining the elevations with the plan in a single drawing is

elegant and informative. Finally, the abstract look of such a drawing is

perfectly in line with the style of the modern art movement.

Here we again have Auguste Choisy the professor

at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées. This plan projection looking up

at a coffered ceiling is from L'art de

bâtir chez les romans. If Choisy had been a professor at the École

des Beaux Arts he would have illustrated this same ceiling with rendered plans,

sections and elevations. Teaching at a school of engineering (bridges and

roads), he instead used measurable projection drawings.

Forty years after the publication of

Choisy’s books, plan projection drawings began to be used by architects for

presentations. The hard, measurable drawings highlighted the machine esthetic of

the modern movement. Above is the Netherlands House by Van Eesteren & Van

Doesburg (1922). It is a nice example of coldly elegant abstraction, in the

service of architecture.

Highrise City by Ludwig Hilberseimer (1926)

shows the degree of machine-like order architects were contemplating in those

days. Admittedly, other drawings of the same project included perspectives from

street level, so there was a recognition that people would actually inhabit

these file drawers.

This stair Interior by F. Jacob (1931)

is visually fascinating, but the design is a bit too complex to understand in a

single drawing. Nevertheless, it has

always been a favorite of mine.

Alberto Sartoris was an Italian

architect who was a member of the Rationalist Movement. He was famous for his

theoretical work and writing, but had few projects actually built. This plan

projection drawing titled “Hermitage” (1933) straddles the line between

architectural drawing and abstract painting.

“Villa Gentinetta”, also by Sartoris (1937),

shows a clean, ink-line drawing style that was copied by cutting-edge

architects 40 years later. Funny how ideas and styles tend to be repeated in

our modern age (not unlike the eclectic rut that the “moderns” revolted

against).

Wilhelm Kreis was a German architect

whose long career began during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and lasted until

after World War Two. Although he designed in an historical conservative style,

he also produced plan projection drawings. In this example of the Army Command Center

in Berlin (1938), traditional shade and shadow (comparable to Elliel Saarinen)

is used to enhance the reality of the aerial view.

In this study for an apartment by Ettore

Sottsass (1950), the information of the plan has gotten more telegraphic than

the Sartoris interior above. It is quite easily understandable as a space

within a building (a trick that I copied 30 years later), but the functions of

the apartment itself are hard to work out from the large sculptural planes that

form its spaces. Generally, I find that the drawing is awkward and unbalanced.

James Stirling’s plan projection

drawing of Cambridge Library (1964) is a clean and informative image which

harks back to Sartoris, 3rd

image above. His architecture might be called “modern with a twist”, in

that he rejected the cold “machine for living” and reintroduced an eclectic art

of design. His materials were modern, but his sensibility was playful.

Charles Gwathmey had a similar view of

architecture, and had a thriving practice in the United States. The drawing of

a house in Bridgehampton, Connecticut, designed when he was 31, shows the

post-modernist flair for mixing graphic patterns and informative reality.

Above is the Hanselman house by Michael

Graves (1969). Its design is typical of the “New York Five” architectural

group, as is the use of plan projection for the presentation. Graves later

became famous for his more colorful “Postmodern” designs, but switched to

models and colored elevations for presenting those projects. (BTW, In the 80s I

rendered his Team Disney Building in Burbank, California, as part of a master

plan.)

Raymond Erith (who died in 1973) & Quinlan

Terry (who is still practicing) designed in a “radical” classical style,

copying historic styles from ancient Greek to Baroque and Neo-classical. These

English architects designed and built in the traditional way, and usually presented

projects in a traditional way, with rendered plans and elevations. This worm’s

eye plan projection view of the proposed Baha'i Temple in Tehran (1976), is

therefore an anomaly. Still, it is a lovely drawing which explains the design

quite well.

The drawing above, titled “Building 3

Buenos Aires,” is by Diana Agrest & Mario Gandelsonas (1977). It is very

much like Wright’s rendering of the T.P. Hardy House in that the focus

of the illustration is tucked into one side of the composition. When you focus

on the design itself at the bottom of the sheet, you get a fairly pedestrian explanation

of an interesting set of stairs and platforms.

Above is a double plan projection

drawing of Kamioka Civic Hall (1978). Arata Isozaki’s take on hard-line ink

drawing is much like Sartoris (see 5th image above); grids are prominent,

and line weight is not varied. By matching views from opposite sides of the

building on the same sheet Isozaki gives a complete understanding of his complex

design.

While Isozaki seems more inclined to

Sterling’s idiosyncrasies, Richard Meier seems closer to the discipline of

Sartoris’ work. The Arts & Crafts Museum in Frankfurt am Main (1979)

features subtle shifts in the grid, but keeps a consistent unifying module. Meier’s

plan projection drawing presents an interesting contrast between the old Villa

Metzler (standing alone) and the surrounding flurry of modernity in Meier’s

design. The modern addition seems to merge well with the hard-line ink drawing.

Meanwhile, the neoclassical Villa Metzler loses much of its sculptural molding

and ornament.

Emulating previous drawing approaches

is for everyone. This cut-away plan projection of the trading floor at the

(then) Republic National Bank Headquarters in New York City (1983) harks back to

Etore Sottsass’ apartment study from 1950.

This plan projection view of Restaurant

Row in New York City (where I was living in the 80s) was done with two

projecting directions to show both sides of the street at once.

This proposed brownstone renovation, was

a presentation board for a freelance job I did with my old friend Ty Kaul. It

was illustrated using a plan projection worms-eye view to show off the colorful

wall and ceiling work.

This sketch was done for a student

project involving the American Stock Exchange. It is a good example of plan

projection drawing as a design tool. The student who designed and drew it is a

talented architect who I worked with later in my career.

Plan projections of simple cubes can be

confusing: am I looking down at the exterior or up at the interior. This

drawing by Edward Jones of the Schinkel Archives (1981) is obviously the

latter, but I admit that it “flips” on me sometimes.

In 1983 I was at McDonough Rainey

Architects, and worked on the new Time Magazine Executive Floor in the Time-Life

Building. The 1983 remodeling included

the concept of recreating the iconic skyscraper’s curtainwall system in the

reception area. To illustrate the idea to the client we decided on a plan

projection with the interior “curtainwall” set into a ghost of the exterior

curtainwall. The drawing combines an understandable plan, a realistic rendition

of the reception area’s forms and materials, and a powerful illustration of the

concept. The art was about 20” x 20”, and was produced using airbrush and color

pencils on illustration board.

This New York Picture and Street Map by Bollmann Bildkarten Verlag, from

about 1984, emulates a technique used to illustrate European cities dating from

the 15th century. The buildings are scalable (the vertical is

exaggerated), but the streets and avenues are widened to show off the

individual buildings. The art was done by Hermann Bollmann, who had previously

created views of many European cities. This map was, and still is an

inspirational work of art for me.

The sketches above are not strictly

plan projections since they separate the plan from the enlarged façade, but

they are close, and I like them a lot. They are from Rob Krier’s Elements of Architecture (1986), and are

another example of the power of this type of drawing in understanding a design

idea.

Above is my plan projection drawing of

a mixed use development proposal in the Tribeca section of lower Manhattan

(1988). The drawing is ink on mylar following a simple pencil block out. An

aerial perspective would have taken a day or two to complete, while this plan

projection took an hour. I know… with CAD modeling any sort of view could be

done in a few hours. Still, a plan projection has a certain elegance that

should be kept in mind when choosing how to illustrate something.

Stanley Tigerman’s Fukuoka Apartments (1989) is a curious example

of this drawing type. It certainly delineates the complex layering of façade

elements and shifting blocks (it reminds me of traditional Japanese “fusuma”

screens stacked on top of one another). On the other hand it has always felt a

bit confusing. Perhaps coloring the different materials would have helped

clarify the drawing. The model of the project and the photos of the final

building explain the design better (well, duh!). I can’t help wondering what an

elevation rendered in shade and shadow would look like.

I will end this long inventory with a plan

projection drawing that is morphing into a more abstract sort of drawing. The project is the Santa Monica Restaurant by the

design firm called Morphosis (1989). It is a typical example of the

Deconstructivist architecture of that time. There have been a lot of words

spilled about the Deconstructivist Movement, but the actual architecture is

always striking (and sometimes even beautiful), in spite of the verbiage.

This drawing, and most of the other

presentation drawings for this project, tend to be “amphibians”; they are both

a representation of 3D reality and a fascinating 2D collage of shapes. The singularity

of the drawing doesn’t always lead to a wonderful design (in this case it did).

The modern movement is no different from the Beaux Art era in this regard; the

presentation drawing is both a means to an end (a building), and at the same

time is a work of art in its own right.

I will be addressing the curious

obscurantism of projection drawing in the next post.