Dynamic Diagonal

The slope of mountains

The shape of sailing ships

The sweep of the Nike “swoosh”

But buildings are usually rectilinear; the cross is a more

architectural pattern… Yes?

Actually, no.

Look down your street.

The tops of the buildings recede into the distance at an angle, a

diagonal. The urban environment is chock

full of diagonals: streets running into the distance, sky scrapers receding

into the sky, roofs angling up like mountain slopes.

But let’s rewind everything here. Diagonals have been found

in compositions for centuries. The diagonal line suggests movement or

perspective. In this regard it is a conflicted pattern; movement is obviously

dynamic, but perspective is the orderly reality of the built environment. The subject of the painting or rendering sets

the tone.

Madame Raymond de

Verninac (above) by Jacques-Louis David mates the diagonal with Hogarth’s

curved “Line of Beauty”, creating a calm, designed look. The lady is not about

to zoom out of the picture frame.

Self Portrait with

palette in hand and wife Martha by Viggo Johansen utilizes the diagonal as

a hidden line on which to hang the faces (and noted palette) of the double

portrait. As with any of the composition patterns, hiding the actual shape is a

good idea.

The painting of Jockeys

in the rain by Edgar Degas uses the diagonal specifically to enhance the

sense of speed and space. It suggests the starting line and the receding

perspective of the race track.

Frederic Remington uses the diagonal shoreline in Moonlight Wolf to counter the centered

subject. The jagged edge of the diagonal gives the scene a certain eerie sense

of foreboding and danger.

Piz Bernina,

Switzerland by Albert Bierstadt, is well balanced and convincing in spite of

the stark abstract quality. The diagonal of the dark foreground is almost as

geometric as a ship’s signal flag, but works as a foil to the brilliant

abstract of the snow covered peaks.

Sticking with the “uplifting” theme, this mountain view by

Edward Theodore Compton marries the typical diagonal with the subtle

atmospherics that I remember from my misspent youth.

This photograph of Grand Central Terminal in New York City

is a perfect example of a static scene creating a dynamic feeling through

perspective. Without the sunbeams, the view would produce a refined, almost

sedate convergence, but with the addition of the angled sunbeams the

perspective becomes an unstoppable march of power.

A similar approach to an image is this rendering by Hugh

Ferriss of a long line of pylons in sharp perspective. It is the Permanent

World Capitol at Flushing Meadow Park in New York City; and if you never heard

of it, you’re not alone.

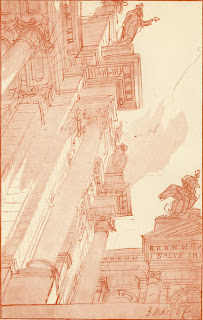

Otto Rieth was a German architect and photographer of the

late 19th century. His ink and wash sketch uses an unusual

perspective to create a curious composition; partly diagonal, partly ‘L’ frame,

all “sturm und drang”.

My small oil sketch of sculpture over a building entry uses

the natural shadow to suggest a line dividing the painting into two equal

triangles.

This architectural rendering of a Residential Building on Logan

Circle by Kai & Ming Hu illustrates the normal streetscape diagonal.

This enticing watercolor of Shindagha in Dubai, UAE by

Michael Reardon uses the perspective diagonals to establish a counterweight to

the detail on the right. The repetition of wedge shapes makes it a fascinating

image.

Michael Reardon also created this aerial of the Officers

Club at Abu Dhabi. He strings a series of sculpted buildings onto a diagonal

seashore. As with his Shindagha rendering, the repetition of shapes, in this

case crescents, makes the image especially interesting.

This unusual “worms-eye” view of the Mabarak Center in

Lahore by Jaroslaw Bieda invites the imagination to wander into fantasy, while

the details bring you back to reality. I see a close-up of a human eye myself.

The linear patterns of our transportation infrastructure

will always show up as a diagonal sweep across an image. This pencil sketch of

the Taipei Pop Music Center Competition by Anthony Grand nests a strong

diagonal into a complex matrix of angular lines.

With diagonals scattered all about the man-made world,

finding the pattern is easy. The trick is to disguise the angle with the busy

detail also found in human construction.

A caveat for all posts on composition.

You don’t

want to produce total chaos.

You don’t

want to create banal order.

You do want

to entice, hint, and suggest.

You want to

create mystery, even if the subject appears to be obvious.

- Composition Part 1 - Architectural Illustration

- Composition Part 2 - The Golden Section & other crutches

- Composition Part 3 - Dark Spot

- Composition Part 4 - Light Spot

- Composition Part 5 - The Cross

- Composition Part 6 - The Pyramid

- Composition Part 7 - Circle

- Composition Part 9 - "L" Frame

- Composition Part 17 - Value Studies

- Composition Part 2 - The Golden Section & other crutches

- Composition Part 3 - Dark Spot

- Composition Part 4 - Light Spot

- Composition Part 5 - The Cross

- Composition Part 6 - The Pyramid

- Composition Part 7 - Circle

- Composition Part 9 - "L" Frame

No comments:

Post a Comment