Several weeks ago Michael Graves wrote an op ed in the New York Times entitled Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing. He very succinctly noted that, in spite of the dominance of computer graphics, the need for hand drawing is central to the practice of architecture. Some excerpts (my emphasis):

“Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets. Drawings are not just end products: they are part of the thought process of architectural design. Drawings express the interaction of our minds, eyes and hands. This last statement is absolutely crucial to the difference between those who draw to conceptualize architecture and those who use the computer.

“The referential sketch serves as a visual diary, a record of an architect’s discovery. It can be as simple as a shorthand notation of a design concept or can describe details of a larger composition. It might not even be a drawing that relates to a building or any time in history. It’s not likely to represent “reality,” but rather to capture an idea.

“As I work with my computer-savvy students and staff today, I notice that something is lost when they draw only on the computer. It is analogous to hearing the words of a novel read aloud, when reading them on paper allows us to daydream a little, to make associations beyond the literal sentences on the page. Similarly, drawing by hand stimulates the imagination and allows us to speculate about ideas, a good sign that we’re truly alive.

Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing by Michael Graves in NYT Sept. 1,2012

|

| Sketch & Elevation of Denver Central Library by Michael Graves, 1991 |

Following are drawings (both site and conceptual) the great

architects throughout history have created in attempting to visualize

architecture. They vary considerably in

style, but are nearly all freehand ink or pencil. There are plans and elevations, but also a

few perspectives. As befits Graves

“referential sketch” recording the “architect’s discovery”, notes describing

the idea are to be found accompanying many of the sketches.

Bernini’s preliminary sketches for the Four Rivers Fountain

in Rome convey the high Baroque vigor of the final design. The sketches also illustrate the structural concept

of the fountain: four freeform Travertine pillars rising to a single mass,

which itself supports an Egyptian obelisk.

Note that the sketches all seem to be from one side of a free standing

sculptural pile; a reminder that most of his other work was designed as a

“stage-set” to be viewed from one angle.

The fountain, in this regard, is unusual for Bernini, and is a striking

work of art viewed from any side. Fun

fact: the fountain was the setting for a scene in the movie “Angles and

Demons”.

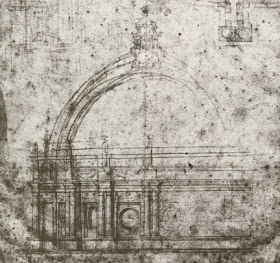

A more architectural example is Michelangelo’s early sketch

for the dome of St. Peter’s. It is a

simple elevation roughed out with pencil and straight edge, but the revised

arcs of the actual dome shows the rethinking that went on during the

drawing. Note the faded plan and

perspective detail at the page top, showing his thinking about the paired

columns supporting the drum.

Charles Garnier was a leading light of the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts in late 19th c France.

This ink “parti”, or conceptual drawing for the funeral of Victor Hugo

shows his emotional, almost gestural approach to design. It also hints at the Beaux-Arts focus on

symbolism and human scale. The projects

of that time might seem grotesque in their symmetrical plans, but their

elevations and details always bowed to the need for human scale.

It is not certain that this sketch of H. H. Richardson’s

Marshall Field building was by Richardson himself, but it certainly was done by

someone so deeply immersed in the concept that “telegraphic” shorthand was

enough to capture both the idea and the atmosphere. The drawing technique was quite common for

1885, being used by correspondents reporting events to their newspapers. In addition to the pencil, black crayon and white ink on cream paper, the artist seems

to have added a hint of brick red to the building itself.

Otto Wagner’s 1894 pencil elevation of the Kunstgalerie is

about 20 inches wide, and shows a loosening of style from the typical

Beaux-Arts elevations. His finished

renderings were an early inspiration for my own work.

Although trained in Beaux-Arts techniques, Louis Sullivan

practiced a thoroughly American sort of design limited only by the strength of

steel and concrete. His reputation is

centered on a lifelong exploration of ornament applied to the modern

“curtainwall”. This pencil sketch of the

Eliel Building in Chicago is done on office stationary, and shows his habit of

playing up the top and bottom of a tower while leaving the shaft as a simple

repetitive window wall.

This letter sized set of ink sketches and notes was done on

the steamship S.S. Friesland in 1897 by Cass Gilbert. Unlike the preceding architects, Gilbert

learned the craft by working for 20 years in Midwestern offices and New York

City. His designs were decidedly

historic, and were deeply informed by the color and texture of natural

materials and building techniques. Look

closely, and read his notes to catch a glimpse of an architect who has mastered

his craft from conceptual design to brick color to construction cost.

Above is a sheet of sketches for the Jubilee Pavilion of the

City of Vienna by Joseph Maria Olbrich.

His brilliant pencil elevations and perspective exemplify the fluid

creativity of the Vienna Secession movement.

His career was unfortunately cut short by leukemia at age 40.

Perhaps the most amazing artistic draftsman among these

architects is Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue.

His pencil site sketches and conceptual doodles have always blown me

away. His ability to clearly and

dramatically illustrate perspectives, elevations, plans and details, seemingly

without effort has always depressed the hell out of me. I really should have a separate post on his

drawings. (the post on his work/life is here)

You can’t have a listing like this without Frank Lloyd

Wright. Although much of the finished

rendering of Wright’s early work was done by Marion Mahoney Griffin, Wright was

quite capable of sketching in plan, elevation and perspective. The letter and ink sketch describing Mr.

Lowell’s house show this ability to describe an idea with style and economy.

Back to the Beaux-Arts.

Whitney Warren’s ink sketch is a typical parti elevation done with

simple economy. The 1910 drawing is only

slightly larger than letter size, but became the basis for the most famous

railroad terminal in the USA. Google the

Grand Central Terminal in New York City to see how close the final building came

to the sketch.

British architectural education ran on a separate, but

parallel track to the French Beaux-Arts.

Edwin Lutyens is perhaps the greatest British architect produced by that

system in the early 20th century.

He had his start building English country houses, but this ink sketch

shows his thinking in regard to the Viceroy’s House in New Delhi, India, in

1912.

Josef Plecnik, like Joseph Maria Olbrich, worked for Otto

Wagner in Vienna, joining the Vienna Secession movement which rejected historical

ornamentation. This cornice study in

pencil and ink shows his ongoing exploration of organic architectural

detailing.

This sketch of the Ingalls Rink at Yale University by Eero Saarinen haunted

me during architectural school. How

could someone take a soft pencil to a lined yellow notebook page, and create such a

spontaneous yet convincing image. Just

amazing… even now.

The study of classical architecture is not dead. Quinlan Terry has continued the traditional

English use of historic idioms popular a century ago. His on site pencil sketch of an arch by

Bramanti shows an eye for detail which is the traditional path to

understanding.

Santiago Calatrava combines the science of engineering with

the art of sculpture to create spectacular architectural forms which continue

the eccentric Spanish design trends developed by Gaudi and Candela. His studies of human and natural forms have

naturally led to similar ink and watercolor sketches of his building concepts,

such as this sketch of Barajas Airport in Madrid.

All of the above examples are of famous architects and

famous projects. But the lowly draftsman

also needs to have the ability to rough out an idea before producing

construction documents. The following

drawings are from the early years of my career when I worked for various

architects as a “pencil pusher”.

First, we have a sketch and development drawing of a service

station in a restaurant. The sketch is

felt tip marker on canary trace, and the dimensioned drawing is drafting pencil

on mylar.

Next is a zoning analysis and massing sketches for a

residential block. It was produced with

graphite pencil on white trace paper.

Finally, there is an elevation study for the Times Square

Tower Competition back in 1984. (Pencil

on trace)

....Which led to a presentation board sketch. (Pencil and color pencil on legal size bond)

....And a final presentation which was one of 8 winners. (Pencil, color pencil, pastel and airbrush on

30”x40” illustration board)

a very thoughtful introduction to "parti". I thought the parti had to be a plan sketch that was "approved" before the student could proceed with developing the scheme over the "semester" be fore being finished up "en charrette" and delivered for final review. I also understand that the submitted design had to obviously be the same design as in the parti sketch

ReplyDeleteYou are exactly right regarding the Ecole des Beaux-Arts definition of "parti". My use of the word is closer to the "concept" that I was taught in school; that is, a guiding idea expressed with plans, elevations, perspective sketches, or any other visual tool. I always liked the practice of quickly establishing a "concept" for a design or painting. I'm less enamored by the rule that the final must match the "parti" sketch.

DeleteGreat, there's so much inoformation to know even I didn't even know few things that I found here. This website - Best 3D Elevation Designers near me also provides so much knowledge about Elevation Design.

ReplyDelete